My thoughts on Vietnam

Introduction

I haven’t posted in a while and I’m intending to write more often. I will start this new era with a non-techincal blog post about my life. In the beginning of May 2025 I went to Vietnam to visit the place my lovely girlfriend was born and raised. I met her amazing family and felt the most welcome I’ve ever been. So the best way to do them justice to my 10-day escapade is to write down my impressions and keep them for eternity in the data pit that is internet (probably will be used to train some AI). I will be detailing my experience in Vietnam through multiple lenses such as: the food, the life, the history and the nature. At last, I will be providing my opinion on my experience and some tips on how to best experience Vietnam if you happen to visit it.

The Welcome

After a long 2-connection flight to Vietnam I got greeted by this, a warm slightly exaggerated welcome by Jamie (aka. Ngoc) and her brother Trong.

.jpg)

This will remain my most memorable welcome by far.

The Food

I can’t be an experience blog post without a description of the food. After all, “a man’s love is through his stomach”.

The Vietnamese cuisine is defined by its harmonious balance of flavors, textures, and colors. The overarching theme centers around freshness and contrast: crisp herbs, savory broths, and vibrant vegetables are paired with tender meats, seafood, and rice or noodles flavored with variants of fish sauce. Except for the savory broths, most of the food is basically unflavored until you dip it in a sauce.

The fish sauce is the heart and soul of the cuisine, providing that umami and salty concentrated flavor. It forms the foundation for many essential sauces, such as nuoc cham (a tangy dipping sauce for spring rolls and grilled meats), nuoc mam gung (ginger fish sauce for poached chicken), and nuoc mam pha (a blended fish sauce for salads and noodle dishes). These sauces, each with their own blend of lime (or green kumquat), garlic, chili, and sugar, highlight the versatility and central role of fish sauce in Vietnamese cooking. I was surprised when I learned that the fish sauce is not a sauce made for fish food, but made WITH fermented fish.

Dishes are designed to be shared, encouraging communal eating and conversation. Whether it’s the iconic pho, fragrant bun cha, or simple street-side banh mi, every meal reflects a deep respect for natural ingredients. For example, the photo above shows the first dinner I had with Jamie’s family and relatives. I was greeted and welcomed by everyone. It was especially surprising the way they shared the food with me. It’s considered respectful to pick up food from the shared dishes and drop it on someone’s plate – I was constantly offered prerolled rolls, from the topmost plate in Figure 2. That was my favorite dish in this picture – it contained pig ears and some green leaves that where put there to be used as the rolling base (same as the rice paper is for spring rolls). In fact, most of the plates come with these large leaves that are used as the roller base.

Bia Ha Noi and the Drinking Customs

The pride of Hanoi is its crafted beer, Bia Ha Noi. This beer has a mere 4.5% alcohol, but my it managed to hit me at 7 glasses. It tastes similar to a white beer like Heineken, but is less bitter and easier to drink. It’s actually pretty light and it doesn’t get in the way of the flavor of the food.

When it comes to drinking, my impression is that people here gather and enjoy drinks together for hours on end. People rarely drink alone; instead, everyone shares the experience. It’s customary to clink glasses with at least one other person, and if only two people are drinking, they shake hands after each toast. I really liked the idea that no one drinks alone—it truly feels like someone is always there to share the pain, joy, or boredom with you. This theme of social life is quite common in Vietnam, and I really enjoyed it. Even though I don’t look Vietnamese, I was welcomed into this social circle and it made me feel at home.

The coffee: Cà phê phin

Of course it can’t be a post about Vietnam without mentioning the coffee. Cà phê phin is traditional Vietnamese way of brewing coffee. It is brewed using a small metal drip filter called a phin. Coarsely ground dark-roast coffee—usually robusta—is placed in the filter, hot water is poured over it, and the coffee VERY slowly drips into a cup below. The process takes several minutes and results in a strong, concentrated brew. It’s often served black or mixed with sweetened condensed milk, either hot or iced. This method highlights bold, earthy flavors and delivers a powerful caffeine kick. As a coffee connoiseur (aka. addict) I have to admit this is by far one of the strongest coffees I’ve ever had. Unlike arabica, this one has a more distict sourness. Below is a photo I took while enjoying a “Chari” coffee at the famous Ca phe Mai in Hanoi. I ended up buyin $60 worth of coffee from them including the “Paris Mai”, which apparently is pooped out by luwak, a squirrel-like animal.

My Favorite Dish: Bánh Cuốn

Bánh cuốn (steamed rice rolls) quickly became the highlight of my culinary journey in Vietnam. For breakfast, Ngoc, Trong, and I decided to ride to a tiny street food shop famous for it. There, the cook skillfully ladled a watery mixture of rice flour onto a thin cloth stretched over a pot of steaming water. The steam, cooked the batter into delicate, translucent rice sheets. These sheets were then filled with a savory blend of minced pork and finely chopped wood ear mushrooms, creating a combination of the squishy rice sheet and the chunky fillings.

The rolls were served with a side of sweet and sour dipping sauce, the same one used on spring rolls, and topped with crisp fried shallots. Each bite was a perfect harmonious dance of crunchy, silky and chunky/squishy textures as well as an elegant balance of sweet, sour, tangy and savory flavors. On the side, we ordered slices of pork sausage dipped in the sauce, complementing each other’s savory flavors. All in all, it was a dish that masterfully mixed flavors and textures beyond what I’ve ever had before.

Bún Riêu: Crab Noodle Soup

This dish is the most colorful and chaotic dish, in my opinion. It’s exactly what its name suggests, AND A LOT MORE. Straight up you will notice a vibrant red broth made from tomatoes and crab paste. The soup is filled with rice noodles, fried tofu, and chunks of crab meat. On top, there are green onions and fried shallots. The broth itself is tangy, slightly sweet, and savory, making it a great comfort food. It was a dish that surprised me with its complexity.

Most importantly in the figure above you should notice the side dish, fried bread. I’ve had fried bread in USA, but this one tases more crunchy. The way to eat it is to just put it in the soup and let it soak the broth – similar to how we eat regular bread in Albania with some stews.

My least favorite: Goat meat

After our boat trip in Tràng An (where King Kong was filmed), in Figure 6, we decided to have lunch in a famous restaurant where they serve goat meat. Unlike Albania, in Vietnam goat is not a common meat, so having a restaurant serve goat meat is rare.

In the photo below, you can see the final spread of all the dishes we ordered. We went with medium-rare goat meat with lime (the shredded one) and goat meat with fried garlic (the chunkier dish). As is typical, both came with a generous side of fresh plant leaves, which serve as a base to wrap and eat the meat with.

Surprisingly, what stood out the most to me wasn’t the food—it was the tea. We tried kumquat tea and a fruit tea, which I believe was dragonfruit. The fruit tea, in particular, was incredibly refreshing—especially after a day of hiking and exploring the ancient imperial capital of Hoa Lư.

Unfortunately, I have to admit the goat meat was a bit underwhelming. It was quite chewy, and since it was cooked with the skin on, it made things even tougher. Even the more shredded dish was hard to get through. On the bright side, the sides really made up for it—especially the little onions, which were a standout.

The controversial: Bún Đậu Mắm Tôm

This dish was amazing. It’s ranked #2 in my personal ranking. I really enjoyed the Mắm Tôm (shrimp paste sauce). The is dish made up of rice vermicelli (bún), crispy fried tofu (đậu), and a variety of accompaniments like boiled pork, chả quế (fried cinnamon pork sausage), and of course fermented shrimp paste–marinated intestines. The centerpiece is the shrimp paste. It’s a pungent, salty, deeply umami dipping sauce. The sauce is divisive even among the Vietnamese themselves due to it’s incredibly stron flavor. The sauce is mixed with lime juice, sugar, and chili to balance its intensity – so when you receive it you have to violently mix it until bubbles are formed. I enjoyed it because it was unique and I don’t plan to eat the pork just plainly boiled like that. After that dish Jamie and her brother gave me their seal of approval for becoming a Vietnamese citizen – I’m on the right track.

The dawg

Staying on the theme of controversy, I’ll now review one of the most unusual dish I tried: dog meat (thịt chó). This traditional specialty, especially common in northern Vietnam, is often grilled and paired with fermented shrimp paste (mắm tôm). The flavor was bold and gamey—reminiscent of goat meat, which is probably why I enjoyed it. My only critique was the chewiness, which stood out even more since I was still partially recovering my sense of taste at the time. In general, Vietnamese cuisine doesn’t seem to shy away from a bit of bite in its meats. Back in Albania, for instance, we tend to pressure-cook goat to make it more tender.

On the ethics of eating dog meat, I don’t side with what I see as selective outrage. I believe all animal life is equal (humans aside), and if someone is comfortable eating an octopus—an animal arguably more intelligent than a dog—it’s hard to justify placing dogs on a higher moral pedestal. Spare me the sentimentality: we are not divine arbiters deciding which species deserve to live and which do not.

Fertilized duck egg: Balut

If you thought dog meat was the peak of culinary controversy, meet balut—a fertilized duck egg with the embryo still inside, boiled and eaten straight from the shell. It’s a common street food, but to Western eyes, it’s the kind of thing that makes people clutch their stomach before they’ve even taken a bite. Below is a picture of a 17 day old fertilized duck egg.

Crack it open and you’re greeted by a mix of textures: tender egg white, rich yolk, and the slightly firmer, delicate crunch of developing bone and beak. Flavor-wise, it’s deeper and more savory than a chicken egg—closer to a meaty broth trapped inside an eggshell. You sprinkle some salt, maybe a dash of vinegar or herbs, and slurp it down while it’s hot.

I liked it. Not in the “oh, it’s weird but I’ll pretend to enjoy it for the story” way, but genuinely liked it. The broth-like richness was addictive, and the mix of textures worked for me. The only reason people recoil is because it forces them to confront the fact that meat comes from living things—something most conveniently forget while buying their sanitized, shrink-wrapped chicken breasts.

As for the morality debates? Please. If you’re okay with eating a full-grown bird, then eating it a few days earlier doesn’t suddenly make you a monster – it arguably spares the bird a lifetime of torture in a cage.

Agriculture

Due to the tropical climate Vietnam bolsters a vast selections of agriculture, many of which are not available in the US or Albania. I had for the first time sugar cane juice (absolutely love it), lychee, mangosteen, jackfruit and even coconut. I really liked mangosteen in particular. It’s a sweet, tangy, and juicy fruit, with hints of peach, strawberry, and citrus.

The nature

The nature in Vietnam is nothing short of fascinating. I came to realize this when Jamie and I went to Ninh Bình. We booked a boat trip to discover the beauties that attacted the movie producers of Kong: Skull Island. While gliding along the calm green waters of Tràng An I was surrounded by towering limestone karsts that rose dramatically from the river like ancient sentinels.

Draped in dense greenery, these cliffs created a scene that felt almost otherworldly, their rugged surfaces contrasting beautifully with the lush jungle below. The moody, shifting skies added a mystical atmosphere, casting patterns of light and shadow that danced across the water’s surface.

Our small wooden boat, hand-rowed by a skilled local boatwoman, moved quietly through the winding waterways. The gentle splash of the oars was the only sound breaking the tranquil silence. Around us, other boats carried travelers in bright orange life jackets, each person lost in awe at the breathtaking landscape. Tràng An’s peaceful beauty and grand scale made it one of the most unforgettable highlights of my journey through Vietnam.

I want to take a moment to acknowledge the wonderful, welcoming, and deeply underappreciated boatmen and women who work tirelessly to show visitors the natural beauty of Vietnam. Their warmth and generosity left a mark on me. After our tour ended, all the rowers gathered to eat the simple lunches they had brought from home. We joined them with our own snacks, and before long they were offering to share their food and asking about my story. It hit me hard, knowing what I’d learned earlier—that they earn barely 200,000 VND (about $7.60) for a single five-hour trip, and even in high season, they might only get one trip a week. Many are forced to take other jobs just to get by. And yet, despite such modest means, they still sat with a foreigner and insisted on sharing what little they had—proving themselves richer than many in the only currency that truly matters: a heart of gold.

The history

When it comes to history, I’ve always been fascinated. Before this trip, though, my knowledge of Vietnamese history was limited to a few YouTube videos and the one-sided perspective of the horrific Vietnam War. Through my dad’s stories, I learned that communist Albania at the time was a strong supporter of Vietnam, with radio broadcasts proudly reporting every achievement of the communist forces against the “imperialist American allies.”

Meanwhile, in the U.S., most of what I learned portrayed the Americans as justified and the Viet Cong as the villains. Given the more recent wars in the Middle East, I’ve come to approach these narratives with a grain of salt. I wanted to learn more about Vietnam’s history before the war to better understand what led up to the conflict, and to hear perspectives on the war from a different point of view.

The French colonialism

Even before my visit, I learned that the French had a major influence on Vietnam. Many buildings in Hanoi showcase classic French architecture, with features like ornate facades, tall arched windows, wrought-iron balconies, and wide boulevards lined with trees. The French introduced European-style villas, grand government buildings, and cathedrals, which still stand today as striking reminders of that era. Walking through Hanoi’s Old Quarter and French Quarter felt like stepping into a unique blend of Vietnamese and European styles. Colonial buildings now house charming cafés, boutique shops, and small museums, all contributing to the city’s distinct atmosphere.

In fact, French influence goes beyond architecture—some Vietnamese food is also inspired by French cuisine. One of the most famous examples is bánh mì, a crispy baguette sandwich that combines French bread, pate (pork liver) with local ingredients like pickled vegetables, cilantro, chili, and various meats or pâté. Dishes like bò kho (beef stew) and pâté chaud (meat-filled puff pastry) also reflect this fusion. It’s fascinating how colonial history has left such a tangible mark on daily life, not just in the buildings and streets, but in the food people eat and the way the city feels.

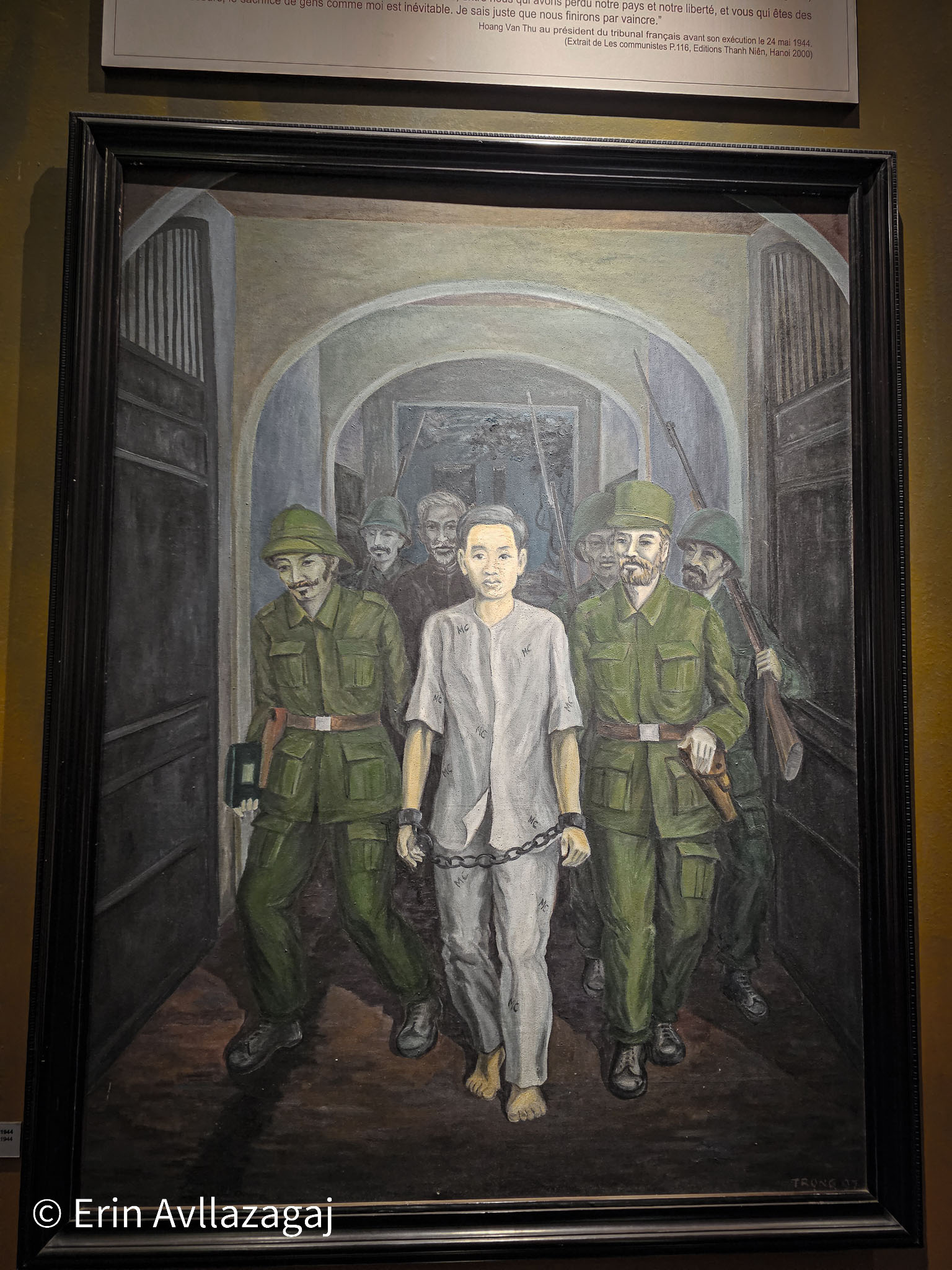

Life under a colonizer isn’t all fun and brioche. In fact, I took my first brush with a grim history lesson from a guided tour of the Hỏa Lò prison in Hanoi (a.k.a. the “Hanoi Hilton”). A small part of this man-made building of horrors is still kept in the heart of Hanoi – reminding the people of the resiliance and strength of their revolutionary freedom fighters.

Hỏa Lò Prison was built by the French colonial administration around 1896 in central Hanoi as part of France’s efforts to consolidate control over Indochina. It was the highest security prison in the area – in fact, they mandated that metal used on the door locks must come from France (Fig.14). The French bought the area for dollars on the dime from the residents of Phu Khánh village, which was well-known as a traditional ceramic and clay pot–making community. Known to the French as Maison Centrale, it was one of the largest prisons in French-occupied Southeast Asia, designed to hold up to 450 inmates but often crammed with thousands. Hỏa Lò was primarily used to detain Vietnamese revolutionaries, nationalist intellectuals, and anti-colonial activists, becoming a symbol of French repression and a rallying point for resistance movements seeking independence from colonial rule.

Many prominent communist revolutionaries were imprisoned at Hỏa Lò during the French colonial era. Ironically, what was meant to break their spirit became a breeding ground for resistance. Inside its grim walls, detainees formed secret study groups to spread Marxist-Leninist ideas, trained one another in political theory, and laid the ideological foundation for Vietnam’s future leadership. Among those held were Trường Chinh, who later became General Secretary of the Communist Party and a key architect of socialist policy in Vietnam, and Nguyễn Văn Cừ, also a Party leader and one of the youngest General Secretaries in its history. Their time in prison was not wasted—it became a period of political consolidation and underground organizing.

Escape stories from Hỏa Lò are legendary and remain a source of pride in Vietnam’s revolutionary narrative. During WW2, when Japan displaced the French colonial administration and occupied Vietnam, the prison system descended into turmoil. As a result, security weakened, and the frequency of successful prison breaks surged. The communist leadership highlights these escapes not just as acts of personal bravery, but as strategic moves that enabled revolutionaries to rejoin the anti-colonial struggle. Today, these stories are preserved as symbols of resilience and the unwavering will for national liberation.

Vietnam war

Naturally, no history of Vietnam would be complete without mentioning the civil war between the North and the South. In Hanoi, reminders of that turbulent period are everywhere—museums, monuments, and preserved war relics. One of the most notable sites is the Hỏa Lò Prison, which includes a section dedicated to its role during the war.

The prison (again)

After Vietnam was liberated from Japanese occupation, the new socialist government took control of the North. The prison was repurposed to hold American prisoners of war. Conditions were reportedly improved from the harsher state left by the French; prisoners had straw beds, access to games, and basic hygiene supplies. In a place under heavy bombing, concentrating prisoners in one location increased their odds of survival since they wouldn’t bomb a prison. This holds true, especially when many Vietnamese civilians were being bombed indiscriminately in the streets. American POWs famously nicknamed it the “Hanoi Hilton.” While the term was used sarcastically, it’s possible that the prison was statistically safer than being outside, where napalm strikes and friendly fire posed threats to GI’s.

The B-52 museum

Another spot worth mentioning for its display of war spoils is the B-52 Museum. As the name suggests, it’s dedicated to the American B-52 bomber—an aircraft that struck both fear and deep resentment into the hearts of the Viet Cong. Bringing down one of these ruthless, indiscriminate war machines was a major morale boost for fighters on the front lines. Back in the 1970s, such victories were even broadcast and celebrated over Albanian radio.

What really caught my attention was how both men and women were trained to operate anti-aircraft gun turrets, with many positioned strategically around Hanoi to protect the city. A detail I learned from Jamie’s dad made the picture even grimmer: to evade radar detection, B-52s would dump massive amounts of metal chaff. While intended to confuse tracking systems, those chunks still rained down on homes below, damaging property and sometimes injuring civilians.

Not only did they rely on anti-aircraft gun turrets, but they also deployed Soviet-supplied S-75 Dvina surface-to-air missiles—far more accurate than manual gunfire, but expensive and limited in number. Designed for high-altitude targets, these missiles were the real B-52 killers, able to bring down bombers before they reached their drop zones. Each launch had to count, as wasting one on a decoy wasn’t an option. When a missile did connect, it wasn’t just a tactical win—it was a statement that even America’s most advanced bombers could be blown out of the sky.

The MiG-21 was one of the North Vietnamese Air Force’s key weapons against B-52 bombers, and it went on to become one of the most produced supersonic aircraft in history. The museum features displays honoring distinguished pilots, complete with their kill counts and the aircraft they intercepted.

At the entrance of the museum, visitors are immediately greeted by a striking symbol of conflict—a destroyed B-52 bomber, a powerful reminder of the war’s enduring impact.

Uncle Ho (Bác Hồ) (aka. Hồ Chí Minh)

Hồ Chí Minh was the figurehead of North Vietnam’s unification war. From what I was told, he was a humble man who rejected the riches and spoils of war in favor of his people—sometimes with a frightening level of efficiency. As I saw for myself, he lived in a modest stilt house built beside a small pond, choosing it over the opulent French colonial governor’s palace just a short walk away. His sandals were cut from worn-out car tires, and his plain khaki suit was worn so often it became part of his public image. He personally read letters sent to him by ordinary citizens, sometimes giving direct orders to solve their problems without waiting for bureaucracy to grind into motion. Even in wartime, he was relentlessly pragmatic—approving strategies that made full use of every available resource, and refusing to waste manpower, supplies, or time, no matter the sentiment attached.

He is still deeply revered in Hanoi today. His body lies preserved in the mausoleum, where visitors file past in silence. After our quiet walk around him, we explored the building where he once worked and met with other leaders. What struck me most was learning that he had maintained good relations with the Albanian government at the time. In Fig. 20 you can see the meeting room where he hosted these leaders—preserved exactly as it was, frozen in time, much like the man himself.

Even the Vietnamese diaspora in France praised his efforts. As a gesture of appreciation, they presented him with a Peugeot 404.

Conclusion

Vietnam is a fascinating country rich in history and culture, home to a resilient and enduring people who have overcome countless challenges throughout the centuries and are in an upwards trajectory of economical growth. Their strength and spirit are deeply woven into the fabric of the nation, reflected in everything from vibrant traditions to rapid modernization. I would strongly encourage anyone to visit this country and experience the culture, tradition and the welcoming of the Vietnamese. I have never felt more welcome in a foreign country, where people would sit down and share their food with you just to hear your story and represent their country in the most positive light they personally could. Here are a few more recommendations from the official website.